In greater Cleveland, federal Covid relief for criminal justice goes mostly to pay police

BY RACHEL DISSELL, ANASTASIA VALEEVA & WEIHUA LI ● NOVEMBER 16, 2022

This article was published in partnership with The Marshall Project, a nonprofit news organization covering the U.S. criminal justice system. Sign up for their newsletters, and follow them on Twitter, Instagram and Facebook.

After The American Rescue Plan Act was signed into law in 2021, Cleveland asked residents and property owners how they would choose to spend the city’s $511 million in federal relief money. About 1 in 5 people who responded to paper and online surveys selected “safety and policing” as a top priority.

“The city needs to hire hundreds more of police officers,” wrote a resident of Ward 6 on the east side. “In order to make that job appealing and to attract high quality, high character applicants, they need to be paid more.”

One west side resident suggested $5 million to prevent crime by creating more programs for young people in schools and recreation centers.

“Once the crimes have been committed,” they wrote. “It’s too late to fix what was wrong.”

The responses pointed to a larger question that local officials in Greater Cleveland, and across the country, must wrestle with as they choose where to spend billions in ARPA relief: What’s the best investment to reduce violence and make communities safer?

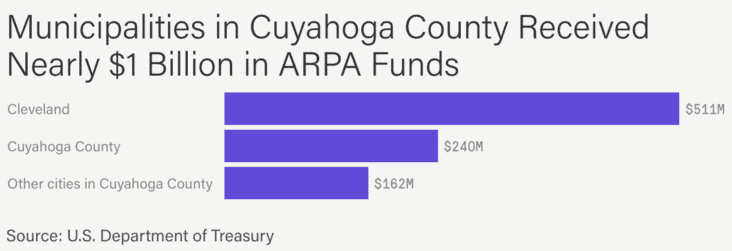

Throughout Cuyahoga County, the federal government has directly allocated a total of $979 million to municipalities in the county and to the county itself, according to data from the U.S. Treasury Department. The state and county also redirected millions in ARPA funding to municipalities.

To estimate criminal justice spending, The Marshall Project reviewed records of state, county and local government allocations and flagged mentions of police, law enforcement, courts, crime or jails. Reporters also searched for criminal justice-related spending in local legislation and state press releases.

Greater Cleveland municipalities saw an infusion of over $190 million in ARPA funds for law enforcement and public safety. About $17 million came through grants from the county and state, while the rest came directly from the federal government.

Like elsewhere, the lion’s share of justice-related ARPA spending here so far has covered payroll for police officers along with buying basic equipment like patrol cars or surveillance technology like cameras. At least $174 million has gone to police salaries, bonuses and incentives for new recruits.

It’s hard to know exactly how much has been spent on community-based efforts to disrupt cycles of violence and address root causes because the categories are vague, and spending descriptions are often broad. But with the majority of the funding going to payroll alone, it’s a small fraction of the overall spending on public safety.

Salaries and Bonuses

Cleveland dedicated about $63 million of its initial ARPA allocation to cover the salaries, overtime, health and dental benefits of police officers. The city also received $4.2 million in state ARPA grants and plans to give $3,000 bonuses to about 1,405 sworn officers, according to a spokesperson.

Cuyahoga County itself has allocated $95.3 million in salaries and benefits for Sheriff’s Department employees, according to a spokesperson, which represents nearly 40% of the money it received from the program. In addition, the Cuyahoga County Sheriff’s office will use $1.5 million from the state for retention bonuses.

Police departments in Cuyahoga County will give out a total of more than $6.5 million in recruitment or retention bonuses, much of which is coming from the state’s Violent Crime Reduction Grant program. That program was created prior to the pandemic with $8 million from the state budget and later supersized with $100 million in ARPA dollars.

At least a half dozen other departments in the county used ARPA money to bolster public safety wages. Cleveland State University’s police department is dividing $240,000 among its officers and dispatchers. Bratenahl, a well-to-do suburb of about 1,500 residents, will split $89,000 in ARPA-funded bonuses among its 11 officers as part of the state violent crime reduction grant — including a $10,000 bonus for Police Chief Charles LoBello.

Technology, Equipment and Facilities

The next largest portion of justice system-related ARPA dollars went to equipment, technology and upgrading police facilities, including dozens of police vehicles and hundreds of video surveillance cameras that will be installed by departments throughout the county.

Cleveland police allocated almost $4.8 million for dozens of vehicles: Chevy Malibus for detectives, patrol SUVs, patrol sedans, Harley-Davidson motorcycles, and one $386,000 armored SWAT vehicle, plus another $3 million to refurbish and upgrade two old helicopters. The city is also spending $6.8 million on hundreds of video surveillance cameras, and police dash cameras.

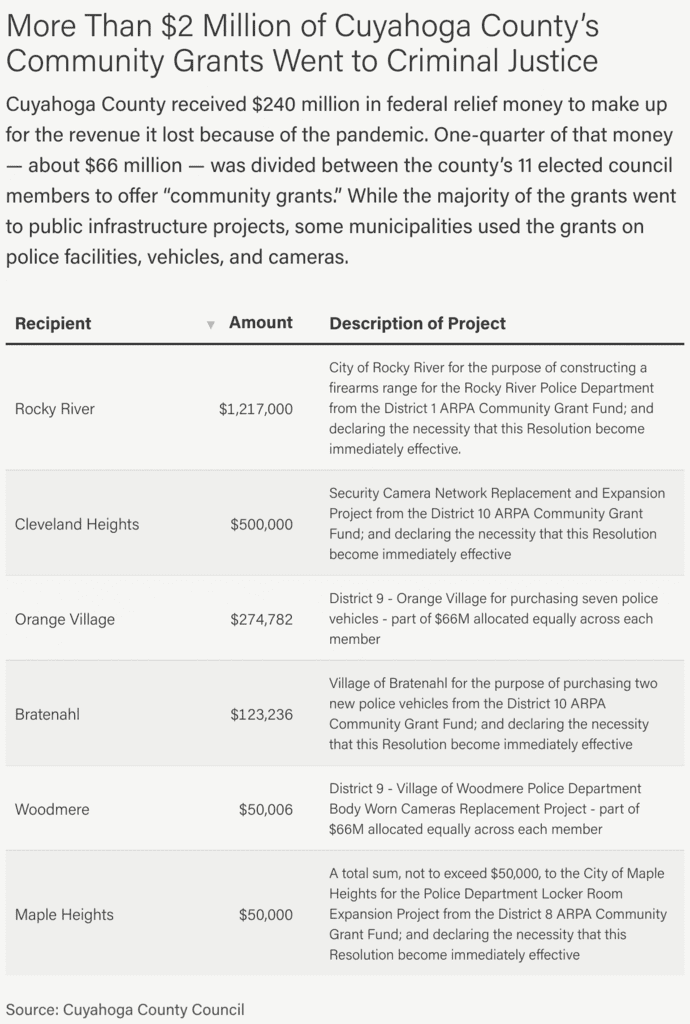

About a quarter of Cuyahoga County’s revenue replacement allocation — $66 million — was divided up between county council districts to be used as “community grants.” That plan resulted in confusion and some criticism because no standard system was created to apply for, distribute or track that spending.

The community grants so far have largely gone to public infrastructure projects, but some of that money also went to local police departments to buy equipment or upgrade buildings.

Orange Village received funds directly from the federal government, and more than doubled their funding indirectly through ARPA-funded grants from the state and county. Police Chief Christopher Kostura said surveillance cameras purchased with a $239,000 state grant help officers catch suspects accused of serious offenses — especially as they travel from one city to another. “When enough people get caught in Orange Village, word gets around,” he said.

Violence reduction

President Joe Biden has promoted ARPA as a way to shore up police budgets, but also as a chance to reduce violence for future generations. “We should all agree the answer is not to defund the police,” he said, talking about the program during his State of the Union address earlier this year. At the same time, he said communities can invest the funding “in more proven strategies like community violence interruption, trusted messengers breaking the cycle of violence and trauma and giving young people some hope.”

ARPA reporting guidelines included the category “community violence intervention,” which cities and agencies have interpreted very differently. Cleveland has categorized spending on police vehicles and cameras as “community violence intervention.”

Cleveland’s leaders have long acknowledged that policing alone won’t solve the problem of community violence. But getting buy-in to actually shift money away from policing has been challenging, said council member Richard Starr, who directed recreation and sports programs for the Boys & Girls Club of Northeast Ohio before he was elected to represent Cleveland’s Central neighborhood a year ago.

“The struggle is that how we are doing things is based on the way things have always been done,” Starr said. He has pushed to put more ARPA dollars toward efforts that help at-risk kids gain mentors, education and job skills. When people pick up guns, he said, “it starts with them lacking resources and support.”

Kate Warren, director of the Greater Cleveland American Rescue Plan Coalition, said the coalition’s priorities are workforce, housing, behavioral health, broadband access, and education — needs they felt were most directly affected by the pandemic, and most likely to make the community safer in the long term. The coalition has advocated for investments in substance use treatment and violence interruption programs, such as the Cleveland Peacemakers Alliance, and for using mental health professionals, not armed police, to respond to people experiencing mental health crises.

Cleveland lawmakers recently approved using $5 million in ARPA money to expand the city’s pilot Crisis Intervention Team co-responder model for three years. The money will go toward doubling the number of officer-social worker teams responding to people experiencing mental health emergencies, as well as paying for a dispatcher and a strategist to oversee the program. The legislation left open the door to “explore opportunities” to implement a community response that isn’t police based.

In September, Cuyahoga County dedicated $2.7 million in ARPA money to Hitchcock Center for Women, which provides drug and alcohol abuse treatment and services and housing for women and their children. Cleveland also pitched in $2 million in ARPA money for a new building in Glenville. “Access to treatment sets people up for success so they don’t have to go into the criminal justice system or, if they have been in the system, they don’t have to keep going back,” said Jason Joyce, executive director at Hitchcock Center.

Deciding the future of ARPA

Participatory Budgeting Cleveland emerged not long after the city’s ARPA allocations were announced in spring 2021. The grassroots coalition wants $30.8 million to be set aside for residents to spend, representing the 30.8% of Clevelanders living in poverty. Cleveland Mayor Justin Bibb has promoted a more modest $5 million Civic Participation Fund that would involve resident input on spending priorities.

At least 200 people attended Participatory Budgeting “porch parties,” including one at Cleveland’s Frederick Douglass Recreation Center on the city’s southeast side. Ashley Burgess, 36, a mother of three and founder of the nonprofit Ashley B. childHOOD ADVOCATE, invited middle and high schoolers in her neighborhood for pizza and to share how “people’s budget should be spent in their hoods.” Their ideas: a new football field, helping the homeless and a Boys & Girls Club.

Unlike older folks in her neighborhood, the ones who own homes and attend ward meetings, “[The kids] don’t bring up the police,” Burgess said, because of the “trust issues and PTSD due to the known history of police brutality, racism, and injustice.”

If it were up to her, Burgess would prioritize meeting the basic needs of young people, and to improve their literacy levels in order to reduce the systematic design of the pipeline to prison.

Cuyahoga County did set aside $5 million to create a Youth Diversion Center, one alternative to offer mental health and substance abuse treatment to kids instead of keeping them in the juvenile detention center, or as County Executive Armond Budish said in a press release, “locked up with murderers or immediately released.” The project has yet to launch.