- Home

- About Us

- Issues

- Countries

- Rapid Response Network

- Young Adults

- Get Involved

- Calendar

- Donate

- Blog

You are here

Honduras: News & Updates

Honduras did not experience civil war in the 1980s, but its geography (bordering El Salvador, Guatemala and Nicaragua) made it a key location for US military operations: training Salvadoran soldiers, a base for Nicaraguan contras, military exercises for US troops. The notorious Honduran death squad Battalion 316 was created, funded and trained by the US. The state-sponsored terror resulted in the forced disappearances and extrajudicial killings of approximately 200 people during the 1980s. Many more were abducted and tortured. The 2009 military coup d’etat spawned a resurgence of state repression against the civilian population that continues today.

Honduras did not experience civil war in the 1980s, but its geography (bordering El Salvador, Guatemala and Nicaragua) made it a key location for US military operations: training Salvadoran soldiers, a base for Nicaraguan contras, military exercises for US troops. The notorious Honduran death squad Battalion 316 was created, funded and trained by the US. The state-sponsored terror resulted in the forced disappearances and extrajudicial killings of approximately 200 people during the 1980s. Many more were abducted and tortured. The 2009 military coup d’etat spawned a resurgence of state repression against the civilian population that continues today.

Learn more here:

News Article

September 4, 2020

Governments all over the world can and must take action right now to reduce the amount of people forcibly displaced because of climate change. According to a United Nation’s Report, we, as a global community, still have a window of opportunity to establish policies and strategies to ameliorate both the issues leading to climate migration and the issues directly caused by climate migration.

News Article

September 2, 2020

We have already emitted enough greenhouse gases (GHGs), such as CO2, to change the very composition of our atmosphere. Scientists, researchers, policymakers, and governmental officials alike know this; they know that the effects of climate change are occurring now and will continue into the not-so-distant future. We now face the question: will we act now to limit the consequences of climate change by reducing emissions or continue with the status quo and suffer the consequences?

Content Page

September 1, 2020

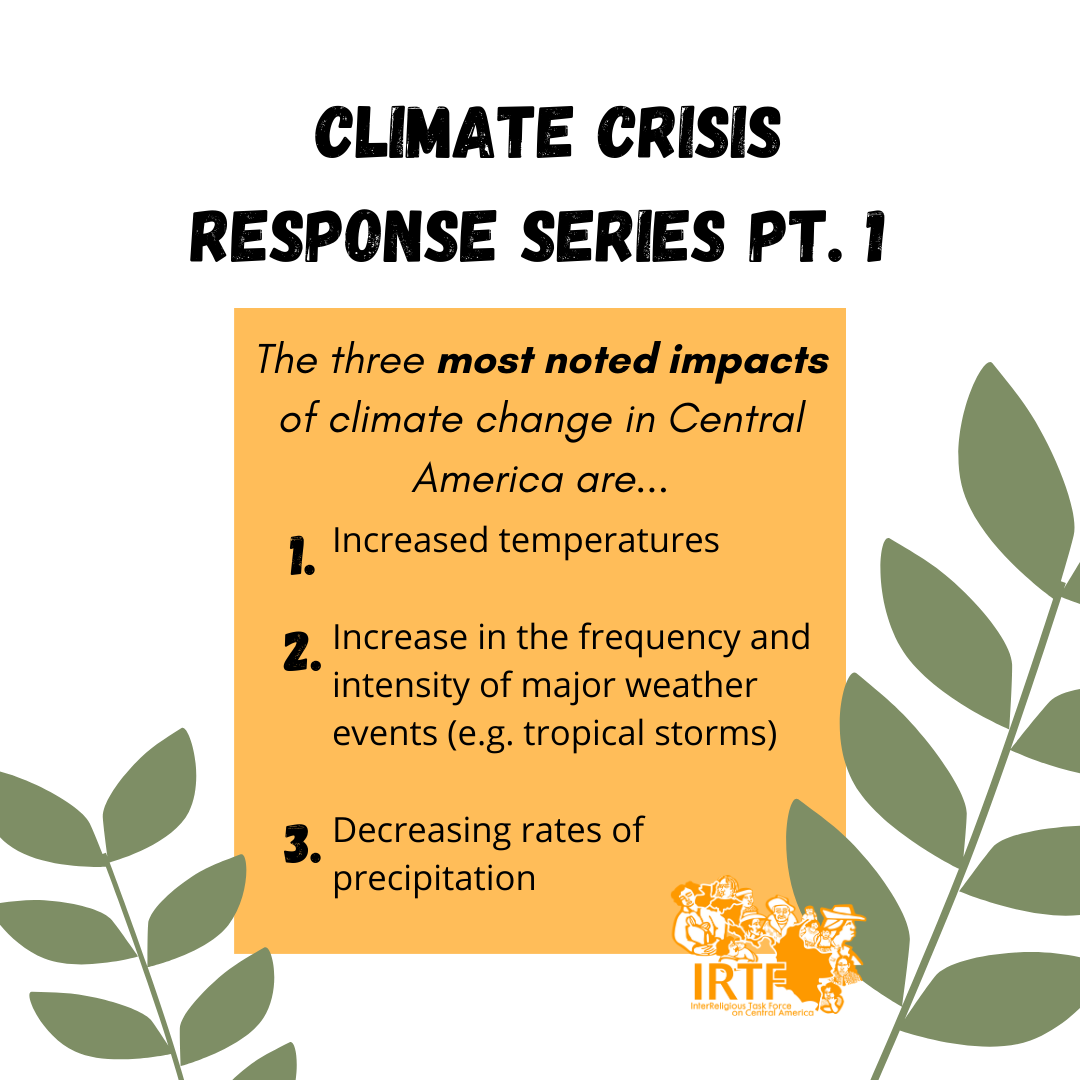

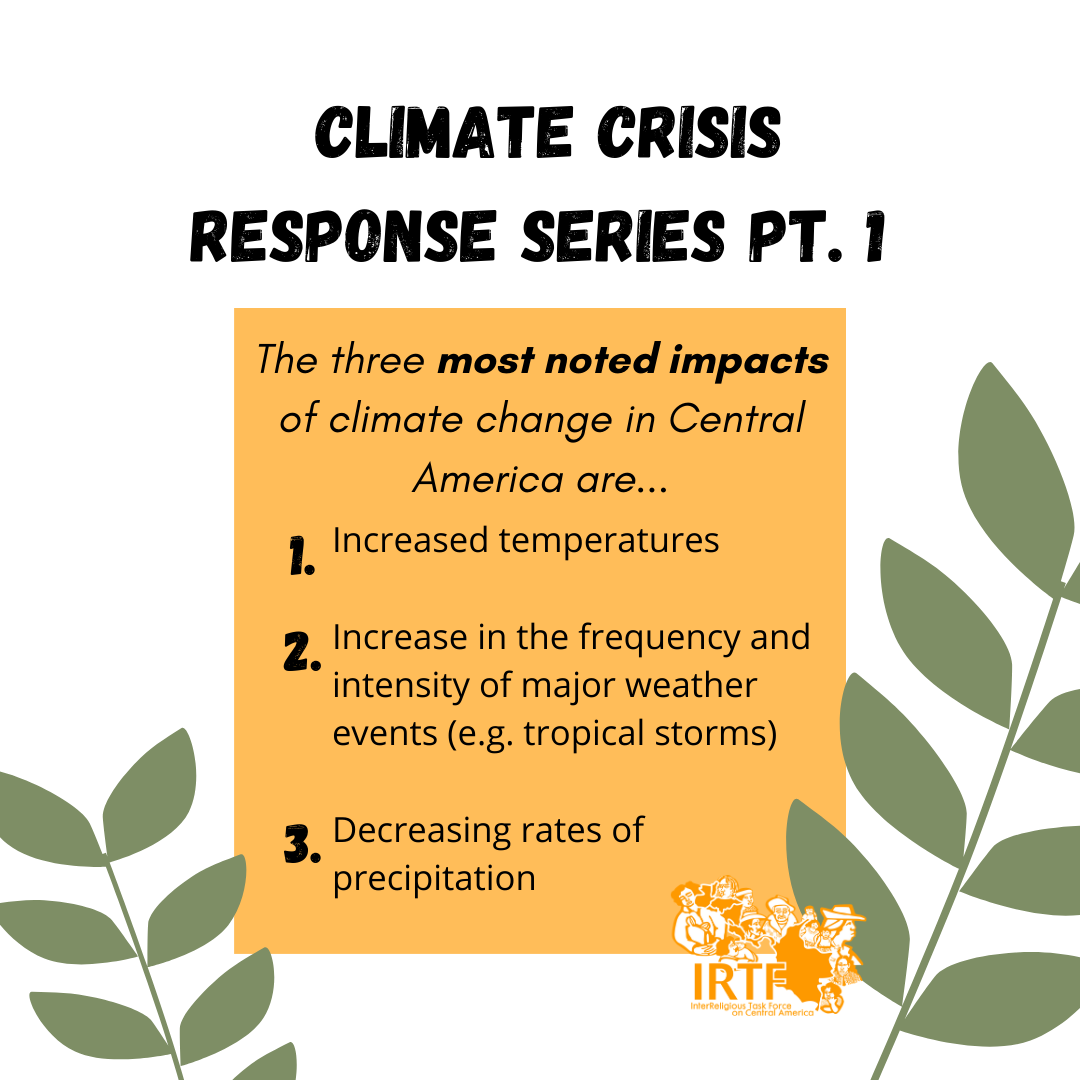

In this series of infographics we explore the ways in which the climate crisis is impacting Central Americans and Colombians, how they are adapting, and how this crisis has created a surge of climate migration.

RRN Letter

August 25, 2020

To bring attention to several identified environmental, social, human, and economic impacts of large scale mining projects in the Atlantic zone, residents of El Guapinol (Colón Department) and surrounding communities organized the Encampment on the Defense of Water and Life in August 2018. They pointed to contamination of the Guapinol and San Pedro Rivers, which supply drinking water to fourteen surrounding communities, caused by an iron ore mine operated since 2014 by Los Inversiones Los Pinares (owners: Lenir Pérez and Ana Facussé). Of particular concern are impacts on the Montaña de Botaderos National Park, which supplies several rivers flowing to Olancho, Atlántida, and Colón Departments. Area residents have documented how the mine is destroying animal life and contaminating smaller waterways. Tens of thousands of inhabitants are at risk of losing their agricultural crops and homes. Because of their actions in defense of the environment, these men have been imprisoned in “preventive detention” awaiting formal charges since September 2019: Porfirio Sorto Cedillo, José Abelino Cedillo, Kelvin Alejandro Romero, Arnold Javier Alemán, Ever Alexander Cedillo, Orbin Nahúm Hernández, Daniel Márquez, and Jeremías Martínez. We demand their release!

News Article

August 17, 2020

At least 212 land and environmental defenders were murdered last year — the highest number since the group Global Witness began gathering data eight years ago. Some 40% of those killed were Indigenous peoples. Today on Democracy Now!, we get an update from Honduras, where the Afro-Indigenous Garífuna community continues to demand the safe return of five Garífuna land defenders who were kidnapped by heavily armed men who were reportedly wearing police uniforms and forced them into three unmarked vehicles at gunpoint. This was the latest attack against the Garífuna community as they defend their territory from destructive projects fueled by foreign investors and the Honduran government. “We are in danger daily — all the leaders of the Garífuna community, all the defendants of the land in Honduras,” says Carla García, international relations coordinator at the Black Fraternal Organization of Honduras (OFANEH).

RRN Letter

August 16, 2020

Carrying a loaf of fresh bread that he was going to deliver to his uncle's house, José Miguel Hernández Tejada set out on his motorbike the morning of August 3. His mother Lizeth Tejada started to panic when evening rolled around and no one had seen him all day. Waiting the requisite full 24 hours to file a missing persons report, she went to the the Las Vegas municipal police department the next morning. Three days later, she was dismayed to discover that the report had never been entered into the computer system. When she later went to the regional office of the Public Ministry, the prosecutor told her that she had no right to file a complaint because forced disappearance was not a crime....We are deeply troubled by these procedural errors (or intentional hindrances) that Lizeth Tejada has experienced during her desperate quest to locate her missing son. We demand swift action.

News Article

August 13, 2020

Rep. Marcy Kaptur of Ohio (OH-09) is among 28 US House members who signed a letter (authored by Rep. Ilan Omar) opposing US investment in large-scale development projects in Honduras that are surrounded by serious human rights, worker rights, and environmental concerns. In their letter to Adam Boehler, chief executive officer of the US International Development Finance Corporation (DFC), the US representatives call the DFC’s planned investment in Honduras “a grave mistake.” They find it “deeply alarming” that Boehler (along with the US Embassy’s chargé d'affaires and the National Security Council’s senior director for the Western Hemisphere) posed for a photograph with President Hernández and announced “an investment in the same region of the country where …disappearances – and years of human rights violations – have taken place.” They make astute criticisms of both the president of Honduras and the energy company behind the Jimalito River hydropower project. “President Juan Orlando Hernández has a record that includes gross human rights violations, credible accusations of electoral fraud, deep connections to narcotrafficking and organized crime, and corruption.” “The company in charge of the project, Inversiones de Generación Eléctricas, S.A. (“Ingelsa”), is credibly accused by local community leaders of corruption, intimidation, and violence [and] the river that is being dammed is the only source of clean drinking water for the communities in the area.” They further note that community members active in organized resistance against the hydropower project have been assassinated, including the young lawyer Carlos Hernández in 2018.

News Article

August 12, 2020

Although the effects of climate change reverberate around the globe, its effects vary from region to region, continent to continent, and Central America is no exception. // Aunque los efectos del cambio climático repercuten en todo el mundo, sus efectos varían de una región a otra y de un continente a otro, y Centroamérica no es una excepción.

News Article

August 10, 2020

“It is the taxpayers of the U.S. who finance the Honduran military and police. If the U.S. stops supporting this narco-state, it will stop violating our rights,” said OFRANEH’s Miranda Miranda, general coordinator of OFRANEH (Fraternal Organization of Black Hondurans). The US State Department describes Honduras as being plagued by “significant human rights issues,” including extrajudicial killings and torture, arbitrary detentions and “widespread government corruption.” And yet in April 2020, Trump decided to gift President Juan Orlando Hernández (who is facing criminal charges of drug trafficking and alleged to have used drug money to rig his election) an extra $60 million in military and security aid. Not only is the Hernández regime not “stopping drugs,” it’s also not curbing illegal immigration to the U.S. In fact, critics say Honduras’ neoliberal policies—policies that cater to transnational corporations at the expense of local residents like the Garifuna—also foster or enable factors like displacement, mass poverty, and the presence of organized crime, all of which actually drive the wave of Honduran migrants headed north toward the U.S.

News Article

August 10, 2020

The Jesuit-sponsored Reflection Research and Communication Team (ERIC) in Honduras reported on Radio Progreso (Aug 10) that “Model Cities” are at the root of the territorial dispossession and violence against Garífuna communities. While he was president of the National Congress in 2013, Juan Orlando Hernández (now president of Honduras) pushed through legislation to create “Zedes,” (Zones of Economic Development and Employment), also referred to as “Model Cities.” Economic forces interested in creating these territorial and administrative divisions (which, by the way, are not subject to the laws of the central government saw a green light for more land grabs of Garífuna ancestral lands along the Atlantic coast. And even though Honduras has been a signatory to the American Convention on Human Rights, it routinely ignores the rulings of the Inter-American Court on Human Rights. This blatant snubbing of international rulings by the State of Honduras is also a blatant discounting of its own constitution: the Constitutional Chamber of the Supreme Court of Justice, the body that interprets the Constitution, says that international judgments are mandatory and must be complied with. The kidnapping of its leaders [on July 18] and the vulnerability that surrounds the Triunfo de la Cruz Garifuna community is the product of structural violence promoted by the State that is expressed in threats, death, cultural and territorial dispossession, according to Dr. Joaquín Mejía, a lawyer and researcher for ERIC. If the State had complied with the sentence in due time, many of the violent atrocities waged in recent years against Garífuna leaders and residents could have been avoided.